SC250Charleston spoke with Dr. James Fichter of the University of Hong Kong, who has a new book, Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, that will be published in 2023. Here Fichter shares some of his insights on Tea Party myths and why tea became such a revolutionary commodity in 1773-1776.

You have written about the American Revolution and American trade for years. Why focus on tea now?

You have written about the American Revolution and American trade for years. Why focus on tea now?

The sestercentennial—250th anniversary—celebrations for the Boston Tea Party in 2023 and the Declaration of Independence in 2026 are massive. They are also instrumental events for propagating or questioning myths. So much about tea, consumption, and the Boston Tea Party story IS myth, that I felt the need to speak to the moment.

What do readers still not know about the Boston Tea Party?

The Boston Tea Party was doubly messed up. It was inadequate and excessive. Customs officials impounded a shipload of Company tea at Boston until it could later be sold, the very act the Tea Party was meant to prevent. The same happened in Charleston. Between the two cities, colonists drank nearly as much East India Company as they destroyed. So it was definitely not the full success we usually believe. But it was also violent, and that violence was divisive. So it was popular with some but excessive to others. George Washington disapproved. So did many Massachusettans. It did not unify colonists or rally them to a common cause. It divided them.

Many women got involved in the tea boycotts and protests. Why?

Yes! Women could engage in politics through consumer protest because women made decisions about how to run the household: what to serve at home, and what to buy at the store. Women were prominent parts of anti-tea rallies. Some wrote in newspapers about the political significance of their role in the boycotts. At the same time, tea was gendered: some of these assumptions still exist today, like the idea that colonial women drank more tea than their menfolk (there is absolutely no evidence for this). Tea parties (the sit-town kind) were polite affairs governed by women, but men—fathers, suitors, or a husband’s business partner—attended, too. Despite the way women could find a public voice in consumer protests, the gender politics around tea was premised on keeping women “in their place.” Patriot propagandists used the idea that women were particularly fond of tea or that tea was somehow effeminizing to rally male colonists. If “even” women could govern their emotions enough to boycott tea, what did that say about a man who did not it boycott? As one writer claimed, tea “has turned the men into women, and the women into—God knows what.”

Boycotts and trade bans sanctions are such a fundamental part of international trade and politics today. How did they work in the American Revolution?

Using your own economic policy to affect the economy somewhere else, in order to then affect that place’s politics is a very indirect way of achieving political change. Even today, when the United States has the world’s largest economy, it often doesn’t work (Cuba is still Communist, after all). In 1770 the North American colonies were so much smaller: Just a quarter the population of Britain, and hardly the main market for British merchants. So, they had much less economic clout. In the end the colonies’ boycott—enforced by the Continental Association—had much less effect on British politics than it had on colonial politics. Showing you adhered to the boycott became a way to virtue signal, or to show your Patriotism. But another way, supporting the boycott became a way to join the “common cause” across the colonies, even if the boycotts themselves were, from a policy perspective anyway, somewhat pointless.

You refer to tea “prohibition” What exactly do you mean? Did colonists boycott tea or did revolutionary authorities ban it?

There were many efforts to boycott tea in 1774, but they weren’t always adhered to, and so Patriot authorities banned tea, beginning March 1, 1775. This was America’s founding attempt at prohibition. Like other bans, including the Prohibition of alcohol 150 years later, or the drug war today, it was not very successful. One of the most interesting way colonists got around prohibition was by getting medical permission to drink tea. Tea was considered to have healing properties, and some medical requests were sincere, but sometimes they were just excuses to get tea. The ban was such a failure, however, that Congress repealed it on April 13, 1776, two months before American independence.

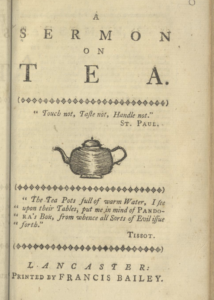

Was there a political discussion of tea and public health?

Tea was one of those subjects where Patriots began with a political conclusion and worked backwards to determine the public health behind it. They decided that tea was politically “bad” and then published essays about how it caused all sorts of ailments, everything from farting to death. It’s hard to know how much colonists believed this. One writer called these “scarecrow stories,” and medical permissions to drink tea (which were approved by local Patriot officials) imply the idea of tea as a health remedy, not a toxin, remained widespread. None of the Patriotic doctors who said tea was unhealthy in 1774 had anything more to say about its dangers when the tea ban ended in 1776.

You talk a lot about “propaganda” in the American Revolution. This is a controversial term in some quarters. Can you explain?

It’s easier to think of the Revolutionary leadership as Founding Fathers rather than politicians. But the Patriots, like their Royalist counterparts—were politicians. They exhorted the public. Sometimes they joked. Sometimes they outright lied. Sometimes they protected military secrets. The Founding Fathers stood up for political ideals. In our efforts to take their ideas seriously, it’s easy to assume Patriots always meant what they said and said what they meant, but taking politicians seriously means asking—do they really mean that? Do they really mean that tea causes mental disorders? Or is that just for effect? A little propaganda can make for good leadership.

You point out that the Revolution did not turn Americans away from tea and that the Tea Party was not part of making America in the way we think. What do you mean?

The American Revolution made the USA, in the most obvious sense, because it created an independent United States. But the cultural revolution, the shift from colonial to independent American identity took longer—at least a generation. The Tea Party and the tea ban didn’t turn Americans away from tea and toward coffee. Americans in 1800 drank at least as much tea, maybe more than their predecessors in 1770. In the Tea Party, Boston Patriots destroyed the tea not only because of issues of taxation without representation but because so many other Bostonians didn’t care about those political issues and just wanted to drink the tea (which they eventually did). The tea bans and destructions were not signs tea was disliked. They existed because tea was still popular.

James R. Fichter is an Associate Professor of European Studies at the University of Hong Kong and the author of Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 (Cornell, 2023), which reveals the hidden history of the so-called Boston Tea Party. Fichter is also the author of So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism (Harvard, 2010) and editor of British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: Connected Empires across the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (Palgrave, Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies, 2019), as well as the author of various articles.