September 2024 marks the 250th anniversary of the opening of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This meeting involved five delegates from South Carolina, who played an important role in the proceedings.

Fueled by rising concerns over Parliament’s imposition of the Boston Port Act in March of 1774, 104 representatives of South Carolina’s General Committee, meeting at the Exchange building in Charleston, elected five of their members to be delegates to the newly called Continental Congress in Philadelphia. The five delegates to this First Continental Congress represented some of South Carolina’s most prominent families and outspoken critics of Britain’s colonial policies. And each of those five delegates had a strong connection to Charleston.

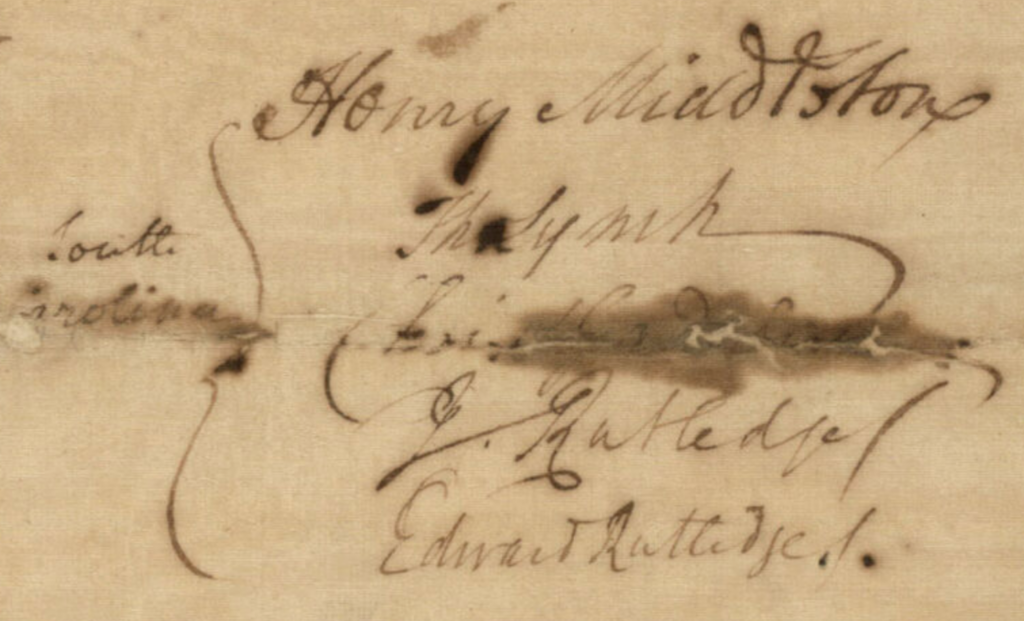

Henry Middleton, Christopher Gadsden, Thomas Lynch Sr., John Rutledge, and Edward Rutledge were instructed by the General Committee to establish a “Union with the Inhabitants of all our Sister-colonies” and cooperate with the other delegates in developing legal measures that would lead to the repeal of the hated “Intolerable Acts” and other restrictions that most felt were highly punitive. South Carolina’s General Committee also agreed that South Carolina would not be bound by any actions that a majority of its delegates opposed.

The five South Carolina delegates sailed to Philadelphia in August 1774, and each would play a central role in the First Continental Congress (September 5 – October 26, 1774)—a gathering that greatly advanced the union between the colonies and worked to set the stage for America’s independence.

Meeting at Philadelphia’s Carpenters’ Hall, the 56 delegates that came together from twelve different colonies formed a Continental Association which established a policy of non-importation and an export ban towards Great Britain, a Declaration of Rights which outlined the colonists’ fundamental rights, including “Life, liberty, and property,” and an agreement to reach out to other American colonies that were not represented. Letters outlining the delegates’ concerns were also sent to King George III and General Thomas Gage in Boston.

One of the key flash points of the congress involved the definition and extent of the proposed export bans. While many delegates, including Christopher Gadsden, preferred a complete and total ban on exports to Britain, Middleton, Lynch, and the two Rutledges vehemently opposed any such restriction being placed on rice and indigo exports. They claimed that this embargo would unfairly harm the South, which relied on rice and indigo exports, both of which the Crown forbade export outside the realm. After walking out of the proceedings, the four South Carolinian planters returned after it was agreed to exempt rice from the export ban.

Let us look at each of South Carolina’s delegates. Four of the five represented Carolina’s powerful and wealthy planter class, while the last, Christopher Gadsden, was the fiery champion of Charleston’s “mechanics” – merchants and manufacturers with voting rights. The oldest – Henry Middleton – was 57 years old, and the youngest, Edward Rutledge, was just 24.

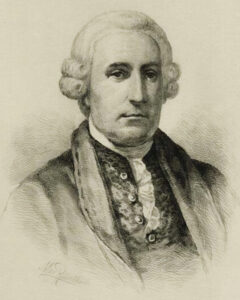

Henry Middleton (57 years old)

Henry Middleton was born in 1717 on his family’s plantation, The Oaks, outside of Charleston. Through inheritances, marriages, and acquisitions, Middleton came to own twenty plantations, totaling 50,000 acres and 800 slaves. Prior to the American Revolution, Middleton had served as a Justice of the Peace and a member of both houses of South Carolina’s colonial legislature.

Beginning in 1763, Middleton became a prominent critic of Britain’s colonial policies and a strong advocate for measures to counteract Parliament’s acts.

In Philadelphia, when Peyton Randolph of Virginia needed to step away for health reasons, Henry Middleton was elected president of the Continental Congress for its final five days. Thus, his name was affixed to many of the important letters that the congress sent to other colonies and King George III.

By all accounts, Henry Middleton adopted a mostly neutral position, with the exception regarding the exclusion of rice and indigo from the export ban.

Middleton was also elected to the Second Continental Congress and served from May 1775 through November 1775. During this session, Middleton helped organize the Continental Army and approved the 1775 invasion of Canada. Despite these bellicose steps, Middleton was opposed to formal independence and resigned his position on February 16, 1776. When Charleston was captured in May 1780, Middleton took the protection of the crown.

Christopher Gadsden (50 years old)

Christopher Gadsden was born in Charleston in 1724. After being educated at an English classical school, Gadsden worked in a Philadelphia counting-house and served as a purser aboard the British warship Aldborough. After returning to Charleston in the late 1740s, he quickly became a successful merchant. By 1774, Gadsden owned four different stores, several merchant ships, two rice plantations, and a large wharf on the Cooper River.

Elected to South Carolina’s lower house in 1757, Gadsden became a leading voice against Britain’s colonial policies. In 1765, Gadsden represented South Carolina at the Stamp Act Congress in New York.

The only non-planter in the group, Gadsden was seen as South Carolina’s representative of its merchants and manufacturers – the “mechanics.” South Carolina’s mechanics, in general, were far more supportive of a ban on exports than the planter class. Assigned to the congress’ committee on trade and manufacturing, Gadsden was a leading voice in denying that Parliament had the power to regulate the commerce of the colonies. During the debates around the creation of a unified ban on imports and exports, Gadsden was far more supportive of a complete ban – a position that created a lasting political breach with the more conservative Rutledges.

In Philadelphia, Silas Deane of Connecticut noted that Gadsden “leaves all New England Sons of Liberty far behind, for he is for taking up his firelock and marching direct to Boston; nay, he affirmed this morning, that were his wife and all his children in Boston, and they were to perish by the sword, it would not alter his sentiment or proceeding for American liberty.”

Regarding the discussion on possible military preparations, Gadsden eloquently declared, “I am for being ready, but I am not for the sword. The only way to prevent the sword from being used is to have it ready …. Boston and New England can’t hold out. The country will be deluged in blood if we don’t act with spirit. Don’t let America look at this mountain and let it bring forth a mouse.”

Like the other delegates, Gadsden was also elected a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. He left Congress early in 1776 and returned to Charleston, where he assumed command of the 1st South Carolina Regiment in the Continental Army. In February 1777, South Carolina President John Rutledge named him brigadier general of the state’s military forces. After the British capture of Charleston in May 1780, Gadsden was initially paroled to his Charleston home, before being transported to St. Augustine, Florida, where he spent 42 weeks in solitary confinement.

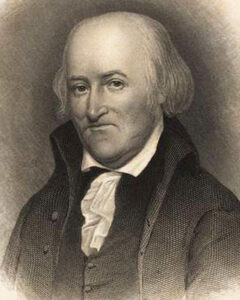

Thomas Lynch, Sr. (47 years old)

Thomas Lynch Sr. was born in St. James Santee Parish around 1727. Lynch’s father was a wealthy rice planter, with several large plantations along the Santee River in South Carolina. Lynch opposed British attempts to limit the colony’s autonomy and was a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765 and elected to the First Continental Congress.

Lynch was the one who proposed that the First Continental Congress meet in the newly constructed Carpenters’ Hall and was the first to nominate, successfully, Peyton Randolph of Virginia as president of the gathering. Lynch was appointed to the committee of rights and grievances and took the lead on authoring the letter to General Thomas Gage in Boston. During the sharp debates on the method of voting, Lynch was an advocate for a plan that would recognize population plus property in the calculations – a plan that was later rejected.

John Adams, a delegate from Massachusetts, wrote that he was “vastly pleased” with Lynch and thought him to be a “solid, firm, and judicious” man. Silas Deane, noted in his diary that Lynch was a “forceful” voice that was “plain, sensible…and above ceremony.”

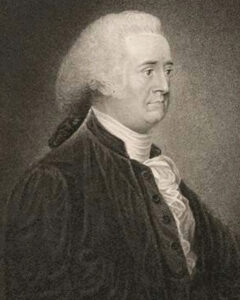

John Rutledge (35 years old)

Born in Charleston in 1739, John Rutledge became one of South Carolina’s most active and prominent political figures. Rutledge took an early interest in law and attended the Middle Temple in London. Rutledge, admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1761, became one of Charleston’s most successful lawyers.

Attending the First Continental Congress with his younger brother, John Rutledge was appointed to the committee on rights and grievances. He argued that colonial rights should be based on the British constitution and colonial charters, not natural law. He also debated against the “Suffolk Resolves” which based allegiance to the king only as a matter of compact.

During the discussion on how to apportion the voting power of the various colonies, Rutledge effectively argued that congress had no legal authority to force the colonies to accept its decisions and that it was best to apportion each colony one vote. This one-colony/one-vote plan ultimately succeeded and was later adopted as the voting structure for the 1777 Articles of Confederation.

John Rutledge, along with the other South Carolinian planter delegates, argued against a complete exportation ban, one that would prevent the export of rice and indigo. He believed strongly that such a ban would unfairly impact South Carolina, who, by law, could not seek markets outside of Great Britain. He feared the development of “a commercial scheme among the flour Colonies” and vowed to prevent South Carolina from becoming the “dupes of the people of the north.”

When it came to military preparations, both John and Edward Rutledge proved to be two of the more conservative delegates. When Richard Henry Lee proposed expanding America’s militias so that British troops would not be required in the colonies, the Rutledge brothers both protested this move as unnecessarily provocative and a move towards possible war with Britain.

John Adams was not an admirer of John Rutledge, writing that he appears to be a man with an “air of reserve, design, and cunning.” But Rutledge impressed Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, a fellow conservative delegate, as an “amiable” gentleman who was willing to consider both sides of an argument and avoided “rash and imprudent measures.”

Rutledge was elected president of South Carolina under the constitution formed on March 26, 1776, and he hurried home to assume these new responsibilities. He was active in organizing the colony and preparing its defenses in the face of growing British threats.

Rutledge was one of four South Carolinians to apply his signature to the U.S. Constitution. He was later appointed by President George Washington in 1795 as one of five associate justices on the newly formed Supreme Court. Rutledge would later become Chief Justice after John Jay resigned to become governor of New York.

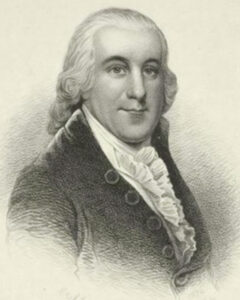

Edward Rutledge (24 years old)

Born in Charleston in 1749, Edward Rutledge was the youngest of South Carolina’s delegates to the First Continental Congress. Like his older brother, Edward trained to be a lawyer. He studied law at the Inns of Court in London and was admitted to the English bar in 1772. His successful defense of printer Thomas Powell, jailed for contempt of the colony’s Royal council, established his reputation as a champion of popular liberty. Edward married Henrietta Middleton, his fellow delegate’s sister.

Many considered the young Rutledge to be too inexperienced to be a delegate. John Adams was entirely irritated by the younger Rutledge, writing that he believed Edward to be very “injudicious,” “excessively vain,” and a “very affected speaker.” Silas Deane noted that he thought Edward Rutledge “a tolerable speaker,” while Patrick Henry of Virginia believed that he and his older brother were likely too conservative and would “ruin the cause of America.” Like his older brother, Edward Rutledge was firmly committed to seeking a mutually beneficial reconciliation with the mother country.

When a more extreme Continental Association called for a complete ban on exports and imports, Edward Rutledge walked out of the congress with three other South Carolina delegates. Concerned over the grave economic impact that a ban on rice and indigo imports would represent, Rutledge argued for exceptions for these two critical South Carolina crops.

The younger Rutledge was also an outspoken advocate for “The Galloway Plan,” which proposed a plan for a union of the colonies that would include a president-general appointed by the Crown. Rutledge praised this plan as almost “perfect,” but other delegates wanted a more independent union. The Galloway Plan was voted down, and the entire debate on this topic was expunged from the official records.

Rutledge would go on to serve in the Second Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776 – becoming the youngest of the signers. Shortly afterward, Rutledge returned to South Carolina and entered the military. Rutledge served as a captain of artillery in the South Carolina militia and fought at the Battle of Beaufort in 1779. After the British captured Charleston in May of 1780, Rutledge was sent to a prison in St. Augustine, Florida, with the other Charlestonian signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Return to Charleston

After the First Continental Congress concluded business and adjourned, the South Carolina delegation returned to Charleston on Sunday, November 6, 1774. That evening the delegates presented the South Carolina General Committee with a copy of the “Extracts of the Proceedings of the Congress.” Later, at the State House, Christopher Gadsden read “An Appeal to the Inhabitants of Quebec” and the “Petition to our Sovereign” – two of the letters that the congress authored and sent.

The biggest challenge that the First Continental Congress delegates faced at home was an explanation for why rice was exempted from the export ban, but indigo was not. Plans were discussed on how proceeds from future rice exports could be used to support the disadvantaged indigo planters. This plan helped to mollify the indigo planters who felt the “Rice Kings” had sold them out in Philadelphia.

The letters of grievance sent to King George III and General Thomas Gage went unanswered, and soon, the American crisis lurched towards open war. Building on the growing sense of union, each of the five South Carolina delegates was elected once more to attend the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

__________________________

Sources

- The South Carolina and Continental Associations: Prelude to Revolution by Christopher Gould, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, January 1986. Published by the South Carolina Historical Society

- The Rutledges, the Continental Congress, and Independence by James Haw, The South Carolina Historical Magazine, October 1993. Published by the South Carolina Historical Society

- The Role of South Carolina in the First Continental Congress by Frank W. Ryan Jr., The South Carolina Historical Magazine, July 1959. Published by the South Carolina Historical Society.

- Christopher Gadsden, Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park. https://www.nps.gov/people/christopher-gadsden.htm

- John Rutledge, Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park. https://www.nps.gov/people/john-rutledge.htm

- Middleton, Henry (1717-1784), South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/middleton-henry-2/

- Edward Rutledge, Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park, Independence National Historical Park. https://www.nps.gov/people/edward-rutledge.htm

- Declaration and Resolve of the First Continental Congress (American Battlefield Trust): https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/declaration-and-resolves-first-continental-congress

- An Appeal to the Inhabitants of Quebec, 1774 (Digital History): https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook_print.cfm?smtid=3&psid=4104

- John Adams diary 22A, includes notes on Continental Congress, September – October 1774 – Massachusetts Historical Society: https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=D22A