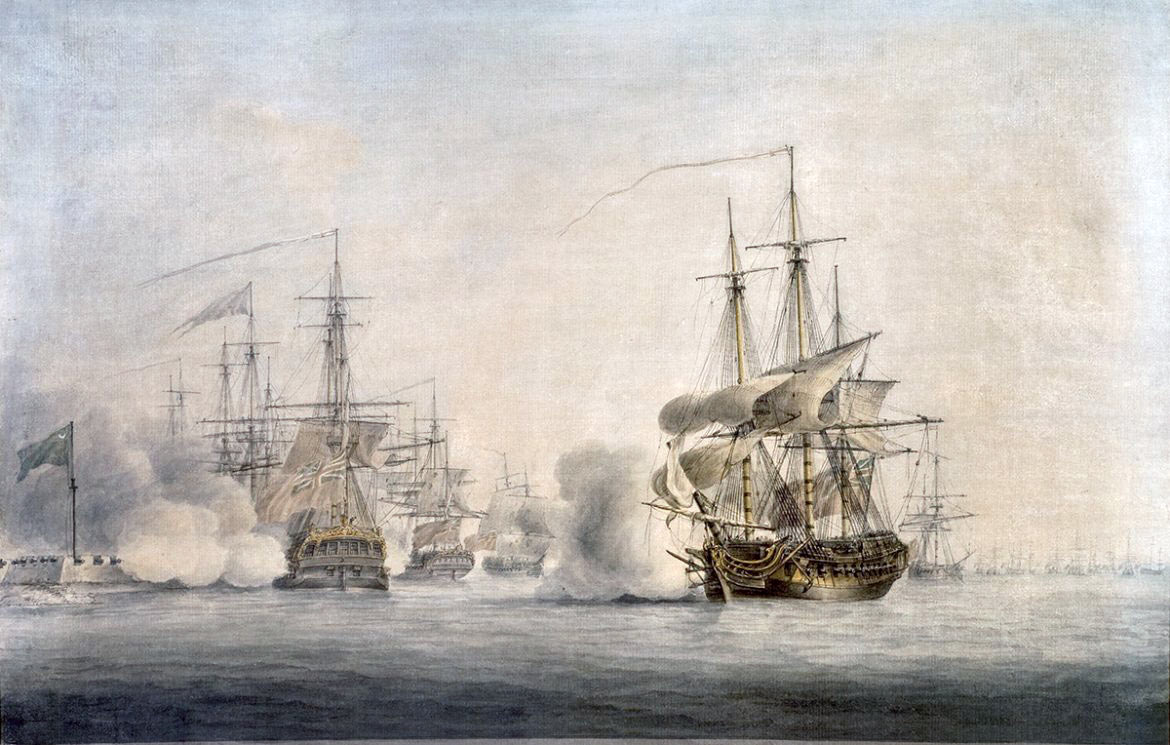

The American victory at Sullivan’s Island on June 28, 1776, drove the British away from Charleston Harbor and dramatically bolstered patriot morale. The sand and palmetto fort at the center of the battle was renamed Fort Moultrie after its redoubtable commander who led the American forces to victory over the Royal Navy and British army.

1. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was the Americans first decisive victory over the Royal Navy in combat.

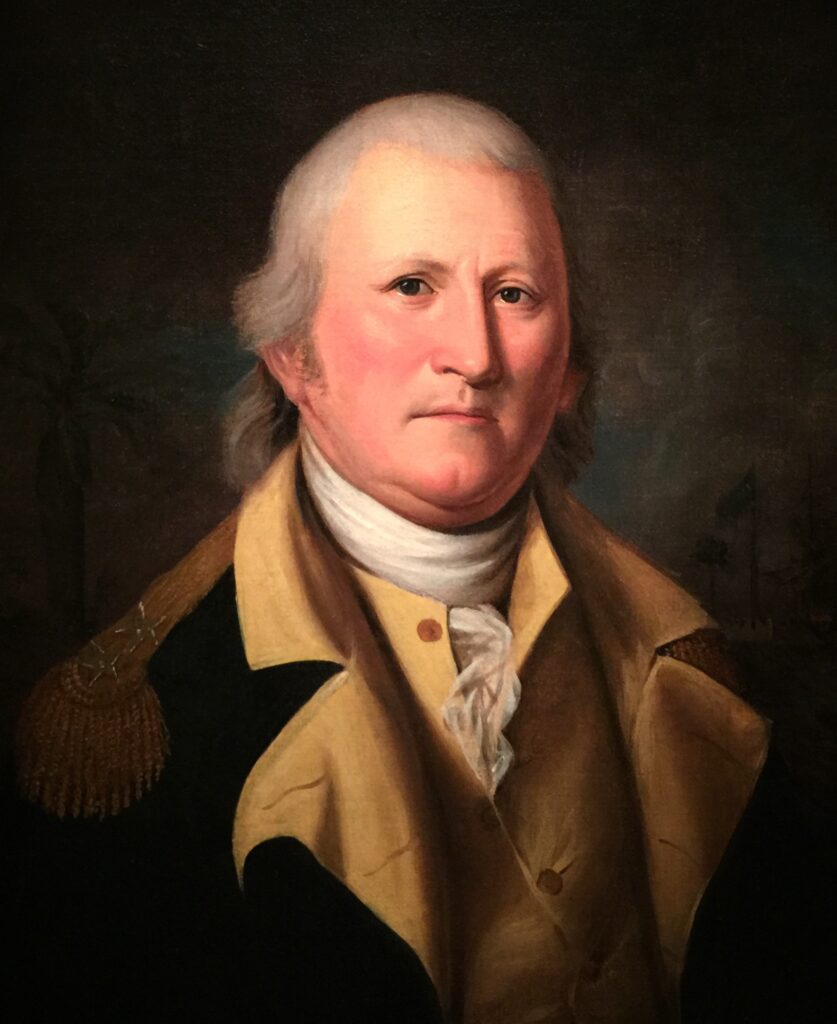

At 11:30 a.m. on June 28, 1776, a combined force of Royal Navy warships and British regiments under the commands of Commodore Sir Peter Parker and Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton began their attack on American positions on Sullivan’s Island. Given their great advantages in firepower and experience, the British were confident that they would swiftly destroy the unfinished fort on the island and seize this strategic location. The lopsided victory by the American forces under the commands of Col. William Moultrie and Col. William Thomson at the battle drove away this British force from the Carolinas and dramatically bolstered patriot morale in the colony. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island became the first decisive combat defeat of the vaunted Royal Navy during the Revolutionary War.

2. Colonel William Moultrie’s superior thought the fort would be quickly destroyed in battle

Major General Charles Lee, the newly arrived commander of the Southern Department, and Colonel William Moultrie’s superior, toured the fort on Sullivan’s Island and determined that it would be quickly destroyed in an attack. Lacking any means of a retreat from the island, and vulnerable to attack from the rear by British warships, Lee declared the unfinished fort as nothing better than a “slaughter pen.” Aware of Lee’s intention to abandon the fort, South Carolina President John Rutledge did not agree with Lee’s views. Circumventing Lee, Rutledge reportedly declared to Moultrie that “You will not [evacuate] the fort without an order from me. I would sooner cut off my right hand than write one.” [1] Despite the fearsome appearance of the Royal Navy fleet off the Charleston bar, Moultrie remained convinced that he could hold this position against attack. He famously declared to another officer that if the walls of the fort were knocked down, his command “will lay behind the ruins and prevent [the British] from landing.”

3. General Charles Lee intended to replace Col. Moultrie on the morning of June 28 – the day of the battle

Not only did Maj. Gen. Charles Lee strongly disagree with Col. William Moultrie about the defensibility of Fort Sullivan, but Lee was also troubled by Moultrie’s tendency to fraternize with his troops and the lax discipline that he witnessed everywhere around the fort. Frustrated with Moultrie, Lee had decided to replace him with Colonel Francis Nash from the North Carolina Continental Line. Nash was to row over to the island and take command on June 28th. But this transfer of command was thwarted by the attack of the British that morning and Moultrie’s fame rising from the stunning victory.

4. A significant intelligence failure greatly contributed to the British defeat

A central part of the British strategy was an infantry attack against the side and rear of the unfinished fort. The British had landed 2,500 Redcoats and 400 sailors under the command of Major Generals Sir Henry Clinton Lord Cornwallis on Long Island (today’s Isle of Palms). Senior British officers had been informed that at low tide their soldiers could easily cross Breach Inlet, the narrow waterway separating Long Island from the northern end of Sullivan’s Island. From there it would be a short march to the fort’s walls.

Unfortunately for the British, reality did not match their faulty intelligence. Rather than being 18 inches deep at low tide, the channel was closer to seven feet in depth – far too deep for any soldier to march across. To make matters even worse, the British had few flat bottom boats to transfer their soldiers across the channel and 780 American soldiers, under the command of Colonel William “Old Danger” Thomson, were dug in behind a palmetto and sand wall with their muskets and cannon aimed at the crossing zone. On June 28, the British dutifully attempted to cross the channel in their boats but were quickly forced back under heavy fire from the Americans. Noting this grand error, Captain James Murray of the British 57th Regiment later wrote that the failure to understand the true conditions at Breach Inlet was “the fatal source of all our misfortunes.”

5. The Royal Navy fired twelve times the number of shells in the battle than the Americans….and still were defeated

Despite Colonel Moultrie’s confidence, there were real reasons for the Americans to be concerned on the morning of June 28, 1776. Commodore Sir Peter Parker’s Royal Navy fleet that attacked Fort Sullivan included the following warships:

Name |

Type |

Guns |

Casualties |

|

Bristol |

Ship of the Line |

50-Guns |

40 killed, 71 wounded |

|

Experiment |

Ship of the Line |

50-Guns |

23 killed, 56 wounded |

|

Thunder |

Bomb Ketch |

8-Guns* |

|

|

Actaeon |

Frigate |

28-Guns |

Ship destroyed |

|

Active |

Frigate |

28-Guns |

1 killed, 6 wounded |

|

Solebay |

Frigate |

28-Guns |

8 wounded |

|

Syren |

Frigate |

28-Guns |

|

|

Sphinx |

Frigate |

20-Guns |

|

|

Friendship |

Armed Ship |

22-Guns |

* The Thunder’s primary weapon was a 13” mortar designed to lob explosive shells on a high arc.

Combined, Parker’s warships carried almost 270 heavy cannons. Opposing this fleet were the 31 cannons inside Fort Sullivan. Both sides could only bring a percentage of their guns to bear in the battle, but the firepower advantage remained decidedly on the British side. Of even more concern, the British fleet was well supplied with gunpowder and could fire at will. Moultrie’s gunpowder stocks, already a low levels, were further diminished by Lee’s order to have half of the fort’s powder transported to the mainland. As such, during the 10-hour battle, Parker’s ships fired nearly 12,000 rounds at the fort, consuming around 34,000 pounds of gunpowder. By comparison, Moultrie’s artillerymen fired roughly 960 rounds at the British warships, consuming 4,766 pounds of gunpowder[2]. Despite this 12 to 1 disparity in fire, the American cannon fire did far more damage to the British than they received.

Given their slower rate of fire, the Americans took careful aim with every shot. Soon American cannon balls and chain shot were striking the warships with regular frequency. Parker’s two largest ships – the Bristol and Experiment – received most of the attention of the fort’s artillerymen and suffered tremendous damage. The Bristol’s captain was killed, and the ship was so damaged that it risked sinking. The Experiment’s captain lost his arm and reported heavy damage to its hull. The Actaeon ran aground in Charleston Harbor and was burned by its crew. And to add further embarrassment to the day, Commodore Parker was wounded on the deck of the Bristol and “suffered the indignity of having the hind part of his breeches shot away, laying bare his backsides.”

In total, the Royal Navy would report 220 soldiers and sailors killed and wounded, while Moultrie reported that the American loses in the battle amounted to 17 killed and 20 wounded[3].

6. The Sabal Palmetto logs and sand used in the construction of the fort gave it a special advantage

Given the decided advantage in British firepower, why did the British suffer far more casualties than the Americans? One significant reason noted by both sides was the materials used to build the fort. During the construction of the fort, thousands of Sabal palmetto logs were floated over to the island and maneuvered into two parallel lines by soldiers and enslaved laborers sent to the site. Between the two lines of logs, sand was packed into the interior. Once completed, the fort’s walls would be roughly 16 feet wide and twenty feet tall. The palmetto logs were spongy in nature and did not splinter easily. When hit, the palmetto and sand walls tended to absorb and disperse the kinetic power of the British cannonballs. The role that these palmetto logs played in the American victory would quickly become the stuff of legend. The palmetto would be featured on South Carolina’s official seal in 1777[4], its 10-Shilling currency note in 1778, at the center of its flag in 1861, the official state tree in 1939, the state pledge in 1966, and today, South Carolina is known as “The Palmetto State.[5]”

7. Fourteen different states feature cities and counties named for one of the battle’s heroes

During the height of the battle, a British cannon ball struck the staff holding aloft the fort’s flag – a blue flag with a white crescent in its top left corner. Noticing that the fort’s flag was no longer flying, many Royal Navy officers wondered if the Americans had surrendered. Determined to restore the flag above the fort, Sergeant William Jasper of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment raced forward atop the parapet. Ignoring the terrible enemy fire that made his exposed position all the more dangerous, Jasper grabbed the downed flag and affixed it to an artillery sponge staff. Jasper’s courageous act emboldened everyone in the fort. Learning of Sgt. Jasper’s act after the battle, President John Rutledge presented Jasper with his own sword. Sadly, Sergeant William Jasper would not survive the war. During the October 9, 1779, Franco-American assault on the British lines at Savannah, Jasper was mortally wounded trying to rescue his regiment’s flag.

During the height of the battle, a British cannon ball struck the staff holding aloft the fort’s flag – a blue flag with a white crescent in its top left corner. Noticing that the fort’s flag was no longer flying, many Royal Navy officers wondered if the Americans had surrendered. Determined to restore the flag above the fort, Sergeant William Jasper of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment raced forward atop the parapet. Ignoring the terrible enemy fire that made his exposed position all the more dangerous, Jasper grabbed the downed flag and affixed it to an artillery sponge staff. Jasper’s courageous act emboldened everyone in the fort. Learning of Sgt. Jasper’s act after the battle, President John Rutledge presented Jasper with his own sword. Sadly, Sergeant William Jasper would not survive the war. During the October 9, 1779, Franco-American assault on the British lines at Savannah, Jasper was mortally wounded trying to rescue his regiment’s flag.

Jasper’s courage was celebrated throughout the colonies. And today, cities and counties in South Carolina, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Minnesota, Tennessee, and New York are named after this humble soldier. In addition, beautiful statues to Sgt. Jasper can be found in Charleston’s White Point Garden and in Madison Square in downtown Savannah, Georgia.

This famous moment from the Battle of Sullivan’s Island has been captured in various works of art over the centuries. But despite Jasper’s fame, there is much that is still unknown about this brave patriot who gave his life to the American cause.

Video: Sgt. William Jasper – South Carolina Hall of Fame (Youtube)

Learn More: Caring for the Family of Sergeant William Jasper (Charleston County Public Library)

8. The British defeat was the subject of a popular satirical cartoon published in London

Accounts of the surprising defeat at Sullivan’s Island soon reached England triggering many critical inquiries and editorials. The battle also found its way into a popular satirical cartoon produced by Matthew and Mary Darly in September 1776. Entitled “Miss Carolina Sulivan – one of the obstinate daughters of America, 1776”, this cartoon was the latest in a series of images highlighting British military setbacks in America. “Miss Carolina Sulivan” features a woman with a fantastic, towering hairdo – a growing fashion trend that the Darly’s loved to target. But beyond the fashion commentary the cartoon also has a clear political edge. Nestled atop Miss Carolina Sulivan’s hairdo are military tents, flags, and a fortress filled with cannon. One large cannon has the words “To Peter” on the barrel. Might this be a reference to Commodore Sir Peter Parker – the defeated commander of the Royal Navy in the battle? There is also a figure of a man that has been hanged on a gibbet. During the battle, Sir Peter Parker reported seeing this scene near the fort. Lastly, and maybe most poignantly, Miss Carolina Sulivan’s face looks just like William Pitt the Elder’s – the longstanding former Prime Minister of Great Britain who passionately argued that Britain should pursue a conciliatory path with its American colonies and that America could not be defeated militarily[6].

Accounts of the surprising defeat at Sullivan’s Island soon reached England triggering many critical inquiries and editorials. The battle also found its way into a popular satirical cartoon produced by Matthew and Mary Darly in September 1776. Entitled “Miss Carolina Sulivan – one of the obstinate daughters of America, 1776”, this cartoon was the latest in a series of images highlighting British military setbacks in America. “Miss Carolina Sulivan” features a woman with a fantastic, towering hairdo – a growing fashion trend that the Darly’s loved to target. But beyond the fashion commentary the cartoon also has a clear political edge. Nestled atop Miss Carolina Sulivan’s hairdo are military tents, flags, and a fortress filled with cannon. One large cannon has the words “To Peter” on the barrel. Might this be a reference to Commodore Sir Peter Parker – the defeated commander of the Royal Navy in the battle? There is also a figure of a man that has been hanged on a gibbet. During the battle, Sir Peter Parker reported seeing this scene near the fort. Lastly, and maybe most poignantly, Miss Carolina Sulivan’s face looks just like William Pitt the Elder’s – the longstanding former Prime Minister of Great Britain who passionately argued that Britain should pursue a conciliatory path with its American colonies and that America could not be defeated militarily[6].

View a larger version of the cartoon at the Library of Congress website.

9. President George Washington toured the battlefield during his 1791 visit to the Charleston area

In May of 1791, President George Washington came to Charleston as part of his expansive tour of the southern states. General William Moultrie, the hero of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, was there to greet Washington. After days filled with parties, visits, balls, dinners, and tours of other Charleston Revolutionary War sites, Moultrie and Washington took a boat to Sullivan’s Island to see what little remained of the old palmetto fort. Accompanied by Gen. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Maj. Edward Rutledge, and Maj. William Jackson, Washington listened intently as Moultrie presented a rich account of the battle. Before returning to Charleston, Washington, Moultrie and the others in their party enjoyed a lunch of wine, fruit, sweets, and cold cuts.

10. The annual Carolina Day celebrations are held on the anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island

The stunning victory on June 28, 1776, was a day that all in South Carolina sought to remember. In May of 1777, The Palmetto Society was formed with the sole purpose of commemorating “the signal and providential Victory obtained by our gallant Troops, over the formidable Fleet and Army of Great-Britain, at Sullivan’s Island.” The Palmetto Society stated “That they will be glad of the company of any gentlemen, Friends to Liberty and Lovers of their Country, who may incline to join them, in commemorating an Action, the most important in its consequences to this State, the most honourable to our Troops, and the most disgraceful to our Enemies, that has been known since the commencement of the present arduous struggle for Liberty.”

Throughout the 18th and early 19th century, the 28th of June was set aside as a day of remembrance and commemoration. Some called the day “Palmetto Day”, and others just used the date. It was only in 1873, after a long post-Civil War hiatus, that the term “Carolina Day” debuted[7]. And it wasn’t until 1912, that the term “Carolina Day” was consistently employed. Today, Carolina Day is still celebrated each June 28th with speeches, a parade of citizens, and a wreath laying at the “Defenders of Fort Moultrie” statue in White Point Garden in downtown Charleston.

Other Interesting Facts About the Battle of Sullivan’s Island

- The American fort on Sullivan’s Island did not have a formal name at the time of the battle. It was informally called Fort Sullivan, Sullivan’s Fort, or Sullivan’s Island Fort

- William Moultrie is now buried near the site of Fort Sullivan (Fort Moultrie)

- Thirty members of the Catawba tribe were part of Col. Thompson’s force defending Breach Inlet

- Major Francis Marion – the Swamp Fox – fought at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island

- The American’s built a floating bridge to connect Mount Pleasant (Pitt St. Pier) and Sullivan’s Island. It proved to be a failure.

- The large 26-pounder artillery pieces at Fort Sullivan were captured French guns that had been gifted to Charleston by the Crown before the Revolutionary War

- The last casualty of the battle was South Carolina’s former royal governor: Lord William Campbell, who was aboard the Bristol at the time of the battle helped lead some of the gun crews below decks. During the battle he was wounded by a large splinter. The wound festered, leading to his death in England in 1778.

Video: The Battle of Sullivan’s Island

Additional Sources

- The Battle of SULLIVAN’S ISLAND and the Capture of Fort Moultrie by Edwin C. Bearss (NPS Report 1968)

- Crescent Moon over Carolina: William Moultrie & American Liberty by C.L. Bragg

- Victory on Sullivan’s Island by David Lee Russell

- The British Are Coming by Rick Atkinson

- The Land Battle for SULLIVAN’S ISLAND, Charles Town, SC June – July 1776 by Kim Stacy, 2014 (Article found in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 92 (2014).

- The General, the Major and the Angel: The Discovery of General Moultrie’s Grave by Stanley Smith (1979). USC Scholar Commons Research Manuscript Series #126. (http://scholarcommons,sc,edu/archanth_books/126).

[1] https://www.tompsc.com/290/John-Rutledge#:~:text=He%20wrote%3A%20%E2%80%9CGeneral%20Lee%20wishes,establishment%20of%20South%20Carolina’s%20government.

[2] Crescent Moon over Carolina by C.L. Bragg, page 78

[3] Many sources state that Moultrie’s losses were 12 killed and 25 wounded and that 5 of the wounded died shortly after the battle.

[4] The Seal of the State of South Carolina: A short history by David C.R. Heisser

[5]https://www.scstatehouse.gov/studentpage/coolstuff/seal.shtml#:~:text=On%20April%202%2C%201776%2C%20the,time%20on%20May%2022%2C%201777.

[6] https://www.lambiek.net/artists/d/darly_matthew_mary.htm

[7] https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/story-carolina-day