One of the unsung heroes of the April 21, 1775 Arms & Gunpowder Raids was Mrs. Mary Pratt, the humble housekeeper at the South Carolina Statehouse.

By Katherine Pemberton

During Charleston’s “Arms & Gunpowder Raids” of April 1775, a widow named Mary Pratt played an important role for the burgeoning patriot cause, although little is known about her life outside of this one event. We do know that Mary Pratt served as the housekeeper of the colonial Statehouse, located at the northwest corner of Broad and Meeting Streets. She lived in a first-floor apartment and had a set of keys to the entire building. Begun in 1753, the building was in use three years later, although it was not fully completed until the 1760s. Once finished, it was considered one of the most architecturally sophisticated public structures in the British colonies. This building served as a hub of legal and political activity for the city and the entire South Carolina colony. It accommodated the colony’s only courtroom as well as legislative chambers for the Commons House and the Upper House and offices for members of His Majesty’s Council. In 1757, the large attic space of the Statehouse was also designated as the royal government’s armory, housing a collection of small arms. These arms were taken out of the locked attic, brought down flights of stairs and were whisked away into the town on the night of April 21, 1775. Mary Pratt saw it all.

During Charleston’s “Arms & Gunpowder Raids” of April 1775, a widow named Mary Pratt played an important role for the burgeoning patriot cause, although little is known about her life outside of this one event. We do know that Mary Pratt served as the housekeeper of the colonial Statehouse, located at the northwest corner of Broad and Meeting Streets. She lived in a first-floor apartment and had a set of keys to the entire building. Begun in 1753, the building was in use three years later, although it was not fully completed until the 1760s. Once finished, it was considered one of the most architecturally sophisticated public structures in the British colonies. This building served as a hub of legal and political activity for the city and the entire South Carolina colony. It accommodated the colony’s only courtroom as well as legislative chambers for the Commons House and the Upper House and offices for members of His Majesty’s Council. In 1757, the large attic space of the Statehouse was also designated as the royal government’s armory, housing a collection of small arms. These arms were taken out of the locked attic, brought down flights of stairs and were whisked away into the town on the night of April 21, 1775. Mary Pratt saw it all.

Mr. John Poaug held the office of “Storekeeper of his Majesty’s Ordnance and Stores in this Province.” According to William Moutrie’s memoirs, the men who converged on the armory during the April 1775 raids demanded the keys to the attic armory from Poaug. The Keeper replied that as an agent of the crown he could not do so, but he also hinted that he couldn’t stop them from breaking the doors open. At 11:00pm, a group of these prominent Charlestonians met at the Statehouse with the aim of removing as many small arms as possible. Dr. Nic Butler relates that “the door showed no signs of being forced open. Perhaps a key had been obtained. At any rate, over a period of several hours, they quietly removed at least 800 muskets with bayonets, 200 cutlasses, all of the leather cartridge boxes, and a quantity of match and gun flints. Imagine a bucket brigade of rebels stretching from the attic of the State House, down the stairs, out the north door of the building, and into the courtyard. Waiting there was probably a queue of carts or wagons ready to shuttle the weapons off to multiple secret hiding places, so the entire cache would not be found if the authorities suddenly interrupted the scene.” At this same time, two powder magazines were also being targeted by the “rebels.”

The next morning, April 22, 1775, Lieutenant Governor William Bull was informed about the night’s activities and immediately convened an inquiry at the Statehouse. He first spoke with the Keeper of the armory, Mr. Poaug, as well as the Deputy Powder Receiver to receive a list of royal losses. Poaug stated that the arms were taken by “persons unknown” but that the doors had not been forced open. It may have been this fact that led Lt Governor Bull to call in Mary Pratt for questioning. After all, she lived on the ground floor of the Statehouse and surely must have seen or heard something? Her reply was noted by John Drayton in his own memoirs. He stated that “although she saw the arms taken away, and the persons who took them, she would not give any information tending to a discovery.” According to Drayton, she stuck to her guns (so to speak) even after being threatened “with the loss of her place, which, was mostly her support.” So, who was this woman who labored within the walls of the statehouse? She was certainly a staunch character who refused to name names even when her livelihood and housing were on the line. It seems that she was able to retain her job until British forces occupied Charleston in 1780 and took direct control of the building. She regained her position in 1783 after the British evacuated. This is where our Mary Pratt exits the written record. There was another Mary Pratt who lived in Charleston during this period and who was buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard in 1798, but that Mrs. Pratt was the wife of merchant Samuel H. Pratt who didn’t die until 1811. This Mary would have lived with her husband near East Bay Street and would not have worked outside the home.

It is not uncommon for mentions of middle class, working women like housekeeper Mary Pratt to be absent from the archival record. The stories of enslaved and free women of color are even more elusive. South Carolina women, like other women residing in the colonies, lived under the British legal doctrine of coverture, meaning once they were married, they had no legal identity. Some married women could do business as sole traders but only with the written consent of their husbands. White middle class widows and elite white women had a broader range of choices, but unmarried women were under the legal control of fathers and brothers and, of course, enslaved women were under the control of their enslavers for life. Inferring from her circumstances, Mary Pratt was most likely a white widow of limited means.

Even though their stories are rare, we do know about some Charleston women during the Revolutionary era who demonstrated that they had a will of their own. Some, like Mary Pratt were sympathetic to the Patriot cause. We know that Elizabeth Heyward, wife of Thomas Heyward Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence openly defied the British during the occupation of the city at her home on Church Street. Mrs. Heyward’s husband had been imprisoned, and she refused to “illuminate’ her house with candles in celebration of British military victories. Her house was attacked and damaged by a mob of loyalists. Another elite white patriot woman Rebecca Brewton Motte had her home at 27 King Street taken over as British Headquarters. Historian Christina Butler in her study of “British Occupied Charleston, 1780-1782”, notes that “Rebecca was so known for her Patriotic gestures and criticisms of the British, including wearing a black mourning dress along with other patriot women during the occupation, that she was ultimately arrested and banished to Philadelphia.” Other Charleston women were loyalists, some penning petitions and claims to have the value of their confiscated property and slaves restored by the crown. Other Charleston women like Mary Brobson defied cultural norms by charting their own course amidst the chaos of war. Mary left her loyalist husband Joseph who published an ad in the newspaper warning residents , “not to harbour or credit on my account my wife Mary Brobson.” He noted that “she went by the name of Mrs. Fleming, at the Sign of the Rebel in Meeting Street, but now goes by the name of Mrs. Thompson.”

Sometimes it’s easier to see the Revolutionary era as a story of great founding fathers and citizen soldiers only. But it’s clear that we should follow the advice of founding mother, Abigail Adams, as she wrote to her husband John in 1776. “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.” In doing so, we can discover the fascinating lives and the experiences of South Carolina women who lived through tumultuous times.

_________________________________

Katherine Pemberton is a board member of SC250 Charleston and is the Education & Outreach Manager for South Carolina 250. Katherine received her BA in Historic Preservation from Mary Washington College. Katherine has worked as an archaeologist, city tour guide, education specialist, preservationist and as a museum director in Charleston for more than 30 years. Katherine also taught a graduate course in Historical Research Methods for the Clemson MS Program in Historic Preservation for nearly 20 years.

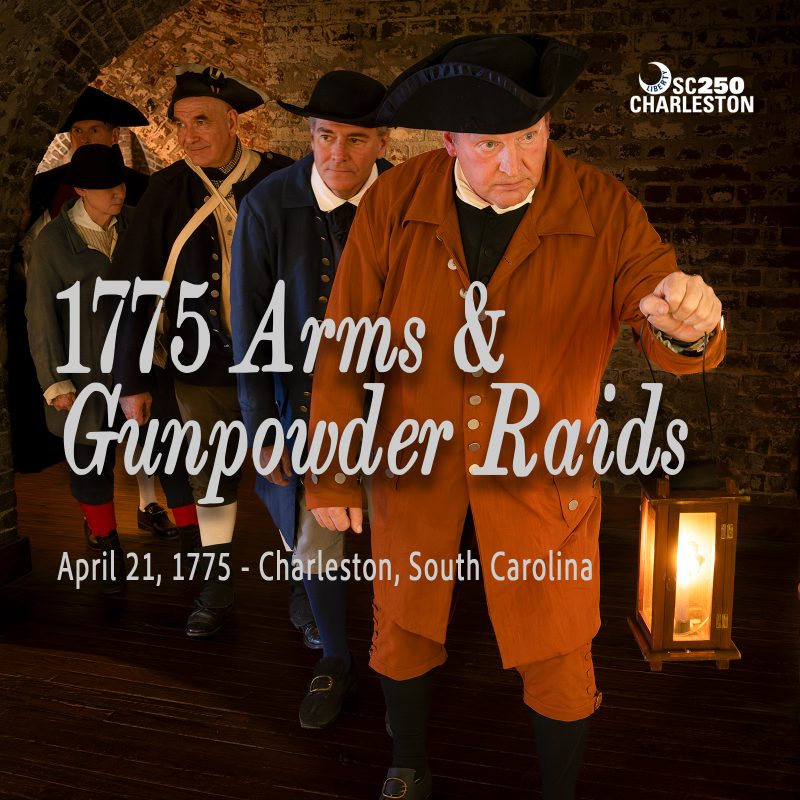

250th Anniversary: April 21, 1775 Arms & Gunpowder Raids

Learn more about the 250th anniversary of the April 1775 Arms & Gunpowder Raids conducted in the Charleston area. This secret operation helped support the Patriot’s move to create armed militias to resist the growing military threat coming from the Crown.